Historical Background

Montana Iron Foundries

Development of foundries in Montana, as

with other manufacturing enterprises, was directly associated with

large-scale mining and ore refining. At first, most of the equipment

needed by the industry was transported by railroad from outside the

region. However, local foundry works soon emerged to provide mining and

milling companies with a quicker and cheaper alternative to distant

manufacturers.

In 1894, reports from the Montana Bureau of

Agriculture, Labor and Industry show that there ere eight foundries and

associated machine shops in Montana; two years later, there were eleven.

In 1897, the number fell to eight, but by 1898 it had risen back to ten.

The 1898 report stated that the manufacture of castings and machinery for

mines constituted the larger part of foundry work, although most of the

work was not done for the larger mines, which had their own machine shops.

During the five years covered by the reports, the number of men employed

in the foundry industry only once rose above 500, in 1896. The foundry

business was a small but important part of Montana industry. For all of

its mineral wealth, Montana never produced significant amounts of iron

ore; therefore, all iron and steel fabricating relied on sources from

outside the State.

Montana's 19th century foundries were

concentrated in established industrial centers, such as Helena, Great

Falls, and Butte. As early as 1886, the Helena Iron Works manufactured

steam engines and farm implements, in addition to mining equipment. By

1896, Great Falls had at least one foundry/machine shop firm, the Great

Falls Iron Works. During the 1880s and 1890s, Butte had several foundries, including the Lexington, Butte Foundry and Machine Shop, and the

Montana Iron Works. One of the early foundries in Butte was Tuttle and

Company, which was founded in 1881. In 1890, Western Iron Works was

incorporated, with a new foundry near the Parrot smelter on the southeast

edge of the city. All of these firms specialized in the manufacture of

castings and machinery for mines and smelters. Montana Iron Works became

particularly well-known for its manufacture of a mine timber framing

machine.

Tuttle Manufacturing and

Supply Company

By 1890, Montana was producing 50 percent

of all copper mined in the United States, and had overtaken Michigan as

the nation's leading source of the metal. ACM (Anaconda Mining Company) had now grown into one of

the great foundations of the copper industry. Marcus Daly, superintendent

and mastermind of the company, oversaw the operation of a vast industrial

complex, comprised of numerous mines on the Butte hill and the smelters in

Anaconda. At the same time, these smelters made up the largest non-ferrous

metallurgical plant in the world.

In the interest of economy and efficient

operation, Daly recognized the logic in controlling all aspects of copper

production, including auxiliary industries. By the mid-1890s, ACM owned

such subsidiaries and departments as an ore-hauling railway, an electrical

power and street railway company, and a brick factory. Daly also realized

the need for another component to his system - a foundry and machine shop

plant.

Several factors probably encouraged

construction of a foundry. In 1889, ACM completed a new addition to its

smelter facilities, called the Lower Works. The sheer size of ACM's

operations created a demand for foundry and machine shop products that

local independent manufacturers could not meet. Products from distant

foundries cost more than those produced locally, and long-distance

railroad transportation inhibited fast delivery of essential parts.

Exactly when Daly made the decision to

build a foundry is unclear, but some time before 1890, he had joined

forces with an industrial contractor named Shelley Tuttle and began

planning for the new factory. They chose a 30-acre tract on the southeast

edge of Anaconda, abutting the foothills of nearby Mt. Haggin. During

early September of 1889, workmen started excavating for the foundations

of various foundry buildings. On December 12, the Anaconda Weekly Review

reported that the machine shops at the Upper and Lower Works and at

Carroll would soon be moved to the foundry. The whole factory was probably

in place by the end of January.

When completed, the complex included a

foundry, machine shop, boiler and blacksmith shop, pattern shop, wareho use

and storage facilities, and an office (Fig. 26). All of the new structures were

built with brick walls, no doubt an attempt to reduce the danger of fire.

The new wooden buildings of the Lower Works had burned upon completion in

March 1889; ACM immediately rebuilt them of steel columns and corrugated

metal, at great expense. The lesson of the great conflagration was applied

elsewhere. Almost all subsequent buildings, including some at the

foundry, were designed to resist fire.

use

and storage facilities, and an office (Fig. 26). All of the new structures were

built with brick walls, no doubt an attempt to reduce the danger of fire.

The new wooden buildings of the Lower Works had burned upon completion in

March 1889; ACM immediately rebuilt them of steel columns and corrugated

metal, at great expense. The lesson of the great conflagration was applied

elsewhere. Almost all subsequent buildings, including some at the

foundry, were designed to resist fire.

On January 27, 1890, Tuttle, Daly, and

Dennis F. Hallahan, one of Daly's business associates, incorporated the

foundry as The Tuttle Manufacturing and Supply Company. The capital stock

of the firm was set at $100,000. In addition to running a foundry, the

men laid out as official objectives the operation of a machine and boiler

works and the sale of hardware, mining supplies and machinery. Although

the business carried Tuttle's name, Daly had controlling interest,

insuring that the foundry would operate more or less as a subsidiary of

ACM. Another manufactory subordinate, the Standard Fire Brick Company, was

also incorporated in 1890.

By the end of 1890, the Tuttle

Manufacturing and Supply Company was in full production. A staff of

molders, pattern makers, machinists and blacksmiths operated the plant

and began turning out all manner of foundry products. The company soon

opened an office and warehouse at the smelter site, between the Upper and

Lower Works.

As the Reduction Works underwent

technological improvements and expansions, the Tuttle Company manufactured

a multitude of metal objects required to maintain operations. This

included all types of machinery replacement parts (especially for devices

such as ore concentrating mills and roasting and smelting furnaces), mill

balls, car wheels, gears and sheave wheels (Fig. 27). Besides iron, the foundry also

made castings of brass (pipe and pum p parts), and fabricated some items

from bar and sheet steel (boilers, trusses, girders) shipped to the

foundry by railroad. As ACM's mills and smelters grew, so did the foundry,

increasing in size and capacity to meet the demand for larger and more

complex metal products.

p parts), and fabricated some items

from bar and sheet steel (boilers, trusses, girders) shipped to the

foundry by railroad. As ACM's mills and smelters grew, so did the foundry,

increasing in size and capacity to meet the demand for larger and more

complex metal products.

True to its stated purpose, the Tuttle

Company expanded into general sales of hardware, machines, and mining

supplies. On August 11, 1890, Shelley Tuttle purchased the stock of goods

and merchandise of the Butte Trading Company for $47,000. By 1891, the

Tuttle Company operated hardware stores in Butte and Missoula. The firm

eventually advertised the sale of heavy mining machinery, such as

Ingersoll Sargeant rock drills, and Knowles and Cameron steam pumps, as

well as domestic items, including Garland stoves and ranges and all types

of home furnishing goods. Sales for 1890 totaled $760,000. In time, the

company began serving customers throughout the northern Rocky Mountain

region.

By the close of 1894, the Tuttle foundry

works employed 175 men, including 60 in the molding department, 45 in the

machine shop, 22 in the boiler shop, 20 in the blacksmith shop, 12 in the

pattern shop, 20 general laborers, and assorted clerks and foremen.

In terms of numbers of workers, the Tuttle foundry was the largest in

Montana.

Furthermore, during 1894, the foundry

manufactured a monthly average of 250 tons of castings, and the boiler

shop fabricated 30 carloads of sheet steel into useful products. The

foundry contributed to the prosperity of the town of Anaconda and became a

source of civic pride while local politicians competed with Helena for the

privilege of becoming the State capital. The Anaconda Standard boasted ...

the Tuttle Company had no superior in the West in terms of facility for

quick work and for meeting every demand made upon it for repairs to mining

or smelting machinery.

Foundry Department of the

Anaconda Copper Mining Company

In early 1896, Shelley Tuttle sold his

share of the foundry, and the Tuttle Company underwent a reorganization.

Michael Donahoe and J.A. Dunlap, both Daly associates, joined the board of

trustees. Stock was reapportioned so that Daly held nearly every share. On

May 27, 1896, the men voted to transfer the ownership of the Tuttle

Manufacturing and Supply Company to the Anaconda Copper Mining Company

for the sum of one dollar.

During 1896, Anaconda absorbed several

other incorporated companies which had always performed functions

essential to Daly's copper production system: Anaconda Water Company,

Anaconda Townsite Company, Electric Light and Power, Street Railway

Company, Standard Fire Brick Company, and the Montana Hotel Association.

Also in the ACM portfolio were coal mines, coke-making facilities and

stores at Belt, sawmills and stores in Hamilton, as well as the Butte,

Anaconda and Pacific Railway which hauled ore from Butte to Anaconda.

According to a 1896 ACM board of trustees

report, ACM had invested $4,755,399 in its various subordinate

industries. The report expressed confidence in the years ahead, stating

that ... now the capacity of these several plants is believed to be equal

to any future requirements. More importantly, ACM received reduced prices

on goods and services from its subsidiary departments and avoided the

problems of having to deal with sovereign firms. In discussing the

company's late 19th century stature, historian Michael Malone called ACM

... one of the great American corporations independent, beautifully

integrated, conservatively capitalized, and astutely managed.

After becoming a department of ACM, the

foundry expanded its productive capacity. By 1896, over 300 men worked at

the plant. Four years later, the number had risen to a workforce of nearly

450. That same year (according to the Anaconda Standard), the foundry made

25 tons of castings daily and over 600 tons each month, a substantial

increase since 1894. Some of the equipment manufactured at the Foundry

Department was of substantial size. For example, Engineering and Mining

Journal reported on December 19, 1896, that the foundry was in the process

of fabricating nine-ton skips (ore containers) to accompany a mammoth

hoisting engine (called the "Aztec") at the Mountain

Consolidated mine in Butte.

ACM also began advertising parts and

equipment for sale to regional mining and milling companies in an attempt

to compete against eastern manufacturers. In 1896, the Foundry Department

distributed its first (and apparently only) catalog. The glossy 262-page

publication noted ... that the association of the foundry to the great

mines in Butte and the famous smelters in Anaconda endowed the factory

with the experience needed to produce superior wares. The catalog

directed the attention of mining men and engineers to the ability of the

department to fill all orders for general mining machinery, which they had

been in the habit of placing in eastern cities. This competitiveness with

eastern manufacturers was echoed in subsequent advertising.

Among the more notable ACM-made products

listed in the catalog was a patented, self-oiling mine car axle (more than

3,000 sets were sold within two years), a variety of mine cars, boilers,

hoists, concentrators, furnaces and ore stamp batteries. And, as the

catalog made clear, the Foundry Department was prepared to furnish the

machinery for any size mill, or contract for the erection of same,

complete, and in running order on the ground. In addition to its own

manufactures, ACM sold such well- known machines and equipment as Buffalo

blowers, Roebling's wire rope, Corliss engines, Pelton water wheels and

Fairbanks scales.

Furthermore, the Foundry Department

fabricated machinery and equipment not included in the catalog. Sometime

near the turn of the century, the plant branched out into production of

implements for gold dredging. Workmen built and repaired gold dredging

machinery for companies in Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, British Columbia and

Utah. The foundry also cast a variety of architectural members and

ornaments, such as store fronts and lampposts, some of which still adorn

buildings and streets in the city of Anaconda.

Aside from boilers, the foundry also made

the plant's most spectacular products. With the aid of a hydraulic

riveting machine, workmen put together girders and smokestacks. According

to an article in the Anaconda Standard in 1900, boilermen had built and

erected the highest self-supporting steel stacks in Butte. The boiler shop

also made ore bins for the mines in Butte, and although there is no direct

evidence showing a connection between the boiler shop and the famous mine

headframes, the shop obviously had the capability to manufacture them. In

fact, a measured drawing that was later discovered in the Foundry

Department office depicts a large steel headframe similar to those in

Butte.

Throughout its history and up until its

closure in 1980, the foundry operated as an integral part of ACM's

gigantic industrial system, fulfilling the needs of mines and smelters as

well as those of independent businesses. It served as one of the largest

and most important subordinate operations, at least in terms of machines,

equipment and manufacturing.

Anaconda Foundry and

Fabricating Company - AFFCO

The Foundry Department of the Anaconda

Copper Mining Company continued its normal operations until the 1960s,

when copper production in the area began to abate. In 1980, ARCO shut down

the Washoe smelter and all subsidiary departments due to world copper

market conditions. Soon after, three private investors, including two

former ACM engineers, bought the foundry and returned it to production. As

AFFCO, Inc., the business fills orders for mining firms throughout the

state, such as the Golden Sunlight mine near Whitehall. The AFFCO complex

has changed little over the past 65 years, although most of the foundry

operations have been updated. The plant remains the oldest, largest, and

most intact foundry works in all of Montana.

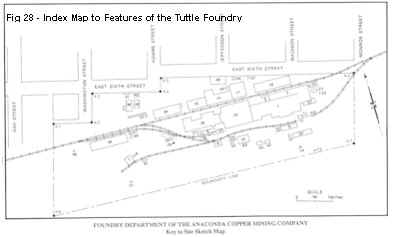

Facilities and processes - The physical

arrangement of the buildings at AFFCO clearly represent the processes

undertaken at the foundry and the movement of materials within the complex

(Fig 28). At the east end of the complex is the main foundry building,

served by a railroad spur which  connects to the mainline of the Rarus

Railroad (formerly the Butte, Anaconda & Pacific). Materials, such as

iron for casting are delivered to this area. The gin pole in the yard and

the overhead traveling crane in the foundry building is used for

unloading. Northwest of the foundry building, facing the street, is the

main office. Employees and visitors pass through the main gate due north

of the office. An employee change house is located next to the gate and

northeast of the office. At the rear of the office are several connecting

buildings: the pattern shop at the east end, a small machine shop next to

the office, and the bar iron storage building to the west. This

configuration corresponds to the operation of the facility. The pattern

shop, where carpenters construct the patterns for castings, is close to

the foundry where the casting takes place; the small machine shop is close

to the main machine shop, which is due west of the foundry and due south of

the office and small machine shop; and the bar storage building is

adjacent to the other shops where stored materials are needed. The large

pattern storage building is north of the foundry and east of the pattern

shop for easy access by workers at both locations.

connects to the mainline of the Rarus

Railroad (formerly the Butte, Anaconda & Pacific). Materials, such as

iron for casting are delivered to this area. The gin pole in the yard and

the overhead traveling crane in the foundry building is used for

unloading. Northwest of the foundry building, facing the street, is the

main office. Employees and visitors pass through the main gate due north

of the office. An employee change house is located next to the gate and

northeast of the office. At the rear of the office are several connecting

buildings: the pattern shop at the east end, a small machine shop next to

the office, and the bar iron storage building to the west. This

configuration corresponds to the operation of the facility. The pattern

shop, where carpenters construct the patterns for castings, is close to

the foundry where the casting takes place; the small machine shop is close

to the main machine shop, which is due west of the foundry and due south of

the office and small machine shop; and the bar storage building is

adjacent to the other shops where stored materials are needed. The large

pattern storage building is north of the foundry and east of the pattern

shop for easy access by workers at both locations.

Materials are delivered to the east end of

the foundry; castings are moved out of the foundry to the west and into

adjoining shops for further finishing and fabricating. Connected to the

west end of the foundry building is the main machine shop. The boiler shop

is connected to the west end of the machine shop. Between these shops and

the office group of buildings, a set of railroad tracks passed to the west

end of the complex, where they switch-backed and climbed the hill south of

the foundry shops so that materials could be delivered to upper levels.

North of the tracks and boiler shop, and west of the bar iron storage

building, is the blacksmith shop. Other free-standing buildings surround

the main cluster of shops, storage facilities and an office. Each of the

surrounding buildings is located in a manner which facilitates the overall

operation of the complex. North of the blacksmith shop are several garages

and a barn, which survive from the period when horses provided an

important mode of transportation. West of the complex is an additional

storage area, in which the oil house, hardware warehouse, and the

foundation of the sheet-metal warehouse are located. The gin pole in this

area was used for moving large objects to and from railroad cars. The iron

breaker and the boiler house are the major buildings on the hill south of

the complex, and they are accompanied by sheds, bins, and shacks for the

storage of tools, lumber, sand, coal, coke and scrap. The sand storage

area is located near the foundry for easy access in the making of molds.

Scrap storage is located near the iron breaker, which in turn, is located

near both the foundry and the machine shop, where quantities of scrap are

both used and generated.

AFFCO has updated many of the operations at

the foundry. The two large cupola furnaces no longer are used to melt

iron. The company has installed new electric furnaces, which do not

violate air quality standards and which allow casting of various steel

alloys. Steel flasks are used instead of wood, and a mechanical sand

conveyor and pneumatic tampers have been introduced for use in making

molds. These changes allow AFFCO to run a much more efficient operation

and to offer its customers a broader selection of steel castings. Despite

these changes, the main buildings in the complex are used much with the

same manner since the beginning of the century.

Selected Bibliography

Anaconda Copper Mining Company (n.d.),Re-

Port of Manufacturing Conditions at the Anaconda Copper Mining Company

Foundry Department, Anaconda, Montana. Anaconda Company Records, Box 172,

Folder G.123: Montana Historical Society Ar- chives, Helena.

Anaconda Copper Mining Company Foundry

Department, 1896, Catalog no. 1: Anaconda Publishing Company, Anaconda,

262 P..

Montana Department of Agriculture, Labor,

and Industry, Reports for the years ending November 30, 1893, 1894, 1895,

1896, 1897, 1898, Helena. Stanley, F.A., 1913, A Large Montana Mining

Machine Shop, in American Machinist, p. 253-259.

Tuttle Manufacturing and Supply Company,

1896, Minute Book: Anaconda Copper Mining Company Records, Box 257, Folder

3: Montana Historical Society Archives, Helena.